22 Feb MAKING A TRIAL LAWYER: How the William Kennedy Smith Trial and Court TV Shaped my Future

Everybody has something that impacts them and guides them along their journey in life. When I talk to lawyers I know, and ask them what made them become what they are, it’s usually something from film or television. For some of the older generation, Perry Mason tends to be a popular response. My younger colleagues will tend to recite for me the closing exchange between Tom Cruise and Jack Nicholson in “A Few Good Men”. Some people can pinpoint the exact event that led them to pursue their career and I am generally wowed by the thing that inspired them so much. I wish I had such a story or could quote the scripted verse of cinematic prose that aligned the stars in such a pattern that would ultimately lead to me pursuing a certain calling, but the truth is my inspiration was much subtler.

I did not know I wanted to be a lawyer until I applied for law school. Hell, I didn’t know I wanted to go to college until I got there. I arrived on the campus of Pittsburg State University in the summer of 1996 with no real plan or direction at all. I was encouraged in all of my pursuits by loving and supportive parents that did not attend a four-year university themselves, and sent me with the declaration that they would support me in whatever I chose to do with my life. I chose football, a sociology major (I didn’t even know what sociology was, but some of the guys on the team told me it was easy.), and a plan to have a good time.

You know how they say, “a funny thing happened on the way to…”, well a funny thing happened on the way to life. Before long I was finding classes I liked, changing my major and deciding to go to…law school? Full disclosure, I’ve always tended to be someone that questioned everything, and I can argue about just about anything. However, there is something else to it as well. I’ve always had a desire to step in the way of a train and save the poor soul that is about to be hit. I don’t know what that complex is called, but I have it. What I didn’t know was that I had become fascinated with the courtroom long before I decided that I wanted to go to law school, and I didn’t want to be a lawyer, I wanted to be a trial lawyer. That happened in 1991.

THE ACCUSATION

On March 30th, 1991 Patricia Bowman met William Kennedy Smith at Au Bar, a night club in Palm Beach, Florida. After some drinks, Bowman offered to drive Smith home. They arrived at a Kennedy family home overlooking the Atlantic Ocean in the early morning hours, and what happened next would be settled months later in courtroom broadcast over the airwaves by the Courtroom Television Network.

William Kennedy Smith is the nephew of then Senator Ted Kennedy, the son of Jean Kennedy Smith. He was with his uncle Ted and his cousin Patrick, Ted’s son. Smith was a fourth-year medical student at Georgetown, but more than that he was a Kennedy. The nephew of a sitting Senator, a slain President, and a slain presidential candidate. In American folklore, he ranks in the highest echelon of admiration, a direct decedent of Camelot.

According to Ms. Bowman, the two decided to take a walk down the beach after arriving at the estate. During this walk, Smith changed suddenly and attacked her, she fled to an area near the pool closer to the house, and it was there that he tackled her and raped her. Smith claimed that they had consensual sex on the beach and it was later that Bowman accused him of rape.

The initial thought was that charges would most likely not be filed. There was no argument that the two had sex that evening, it appeared to be ones word against the other, and one of those persons just happened to be from one of the most powerful families in the country. However, Ms. Bowman did have one person on her side that believed her above all else, Moira Lasch.

Lasch would be the prosecutor to take on the American prince. By the end of the trial she would be called “Maximum Moira” and “The Ice Princess”. She was a career prosecutor and at 40 years old would be world famous as the first prosecutor to have their skills televised across the nation. The only reason you don’t know her name today is because Macia Clark relieved her of a lifetime of national infamy.

Across the aisle would be famed defense attorney Roy Black. Black was an experienced and famous Florida criminal attorney. His appearance in the case alone led many to believe that the prosecution had graduated from a difficult to impossible task.

Lasch did have a plan. She wanted to show the jury that Smith was a habitual predator. That his attack of Bowman was not an isolated incident, but rather an ever-increasing pattern of sexual violence. She planned to present three other women that claimed that Smith had attacked them between 1983 and 1988. Before she could present these witnesses at trial she had to present them to the court at a pretrial hearing.

At that hearing Judge Mary Lupo listened to the allegations of the women, but determined that their testimony did not demonstrate a discernable pattern of behavior to allow the testimony in. This was a massive defeat for the prosecution. Lasch would decide to employ a different tactic at trial, and move on without the three witnesses, the defense would be lying in wait, and the cameras would be rolling.

So, this is where I come in. In 1991 I was 13 years old. In December of that year the Courtroom Television Network (Court TV) would televise an actual jury trial for the first time. Court TV was owned but cable television entrepreneur Ted Turner, creator of CNN. The summer before Al Wagner (My Pop) had made a purchase for his family. He acquired a satellite dish. I helped my dad install the 8-foot black, metal, mesh, concaved monstrosity in our backyard that summer as our dog, Midnight, looked on in wonderment. With the help of this amazing new technology, a whole new world was opened up to me, and that December I would become intrigued with the trial of William Kennedy Smith. The whole thing was shot in real time and then replayed later that day after I would arrive home from school.

It was so interesting to see real people on television doing real things. They looked different than anything I had ever seen. They weren’t acting, and the real-life events that were playing out on TV didn’t jump just to the interesting parts. What the public saw was not pieced together by the skilled hand of an editor, what came across the screen was real, and those things that would have been cut for their monotony was left to be viewed. The rawness was exciting.

THE TRIAL

When Lasch rose to address the jury on December 2, 1991, she was all business. She was direct. She explained in detail how William Kennedy Smith had attacked, then chased down __________ (Court TV would bleep Bowman’s name to protect her identity, when she testified the network would famously put a blue dot over her face), and violently raped her. Her words were like a hardwood and her face offered no emotion, but rather a noticeable lack of it.

Black, on the other hand, approached the jury very differently. It seemed as though he knew them. He spoke like he was entertaining guests a dinner party honoring his client. He carefully and politely whisked away the accusations as that of fancy, a ruse that they would all be expected to entertain, but couldn’t really accept as truth. He was on television, but he didn’t appear to have to comfort of an actor, rather it was something more real than that. He wasn’t acting, he was storytelling, and he liked the story he had to tell.

The prosecution would call a friend, Anne Mercer, that had witnessed Bowman appear “messed up” and “shaking” that night after she returned to the compound from her walk on the beach. Mercer would testify that Bowman had said that evening that she had been raped by Smith. Her testimony was effective and solidified the prosecution’s timeline and most importantly that Bowman had declared that she was raped shortly after she and Smith returned to the home.

Roy Black would destroy Mercer on cross-examination. He blew large gaping holes in her testimony that were supported by inconsistent statements she had given the police. Her inconsistencies called into question whether Bowman had ever claimed she was raped that night, and even led to fantastical tales she had told and now denied that Smith had raped Bowman on two occasions, one of which Senator Kennedy watched. The most shocking moment came when Black let loose on Mercer for desire to sell her story. Audible gasps escaped from the jury after she disclosed that she had sold her story to the television program “A Current Affair” for $40,000.00. When she left the stand, the prosecution was back to square one.

It was always going to come down to the two principles. Patricia Bowman took the stand to testify that William Kennedy Smith raped her. She would refer to the defendant as Mr. Smith at first and then later “that man”, she described the alleged assault saying, “I thought he was going to kill me.”

I expected Roy Black to attack Bowman. I expected to see him impale her with her own words and some expectation that he would present a one-armed man in the audience as the real culprit at the end of his examination. Even in my own 13-year-old world I knew there would be no one armed man, but rather just vicious frothy mouthed attack lines. I started to feel sympathy for the small voice behind the blue dot before Black even began.

The exact opposite happened. Black did point out Bowman’s inconstancies, her memory lapses, and her possible motivations, but he did it in an almost gentle way. He seemed to be more sympathetic for the woman than the prosecutor. Where Lasch was hard and to the point, Black was almost kind and understanding. When Bowman would begin to become emotional, Black would request the court for a recess so that she could compose herself. It was as if he were saying, “I don’t believe you, but I understand you.” By the end of his examination the witness was confiding in Black, telling him of her troubles with men and one-night stands.

Lasch called Senator Kennedy to the stand. She had decided that she would sully the defendant with the escapades of his family. She attempted to bring in the Kennedy name as a motivation for Smith’s lack of respect for women like Bowman. The plan backfired.

The experienced politician used his time on the stand as an opportunity to recall the tragedy his family had seen all in service of a nation that adored them. Lasch wanted to show the jury a pattern of despicable behavior of the haves preying on the have-nots, what she got was Camelot. She wanted Chappaquiddick, she got John John saluting his father’s horse drawn Herse.

The defense would call expert witnesses that would claim Bowman should have been heard screaming by people inside the compound, and scientist that concluded the sand in her underwear came from the beach, when she said she was raped in the grass near the pool. The expert witnesses seemed like they were important, but at the same time they just appeared to have been luxury. They were paid by the defense and presented by the defense, sure their testimony meant something, but it didn’t tell the audience what really happened between Bowman and Smith.

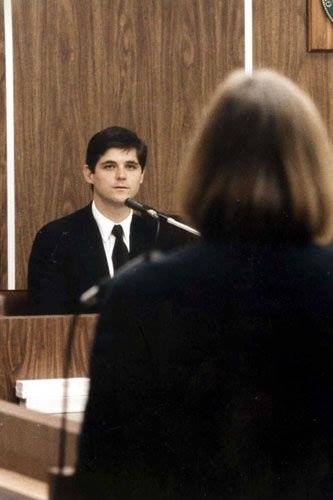

Smith took the stand and testified on his own behalf. It took him only 29 minutes to tell his story, and he did so with a calm poise. He told it as if relaying the events of an otherwise uneventful evening. Nothing happened in his story that seemed surprising or unexpected, Black had already told the jury what they were going to hear in his opening statement, and that’s exactly how Smith put it.

Lasch would cross-examine Smith and solidify the perception that she was the lesser skilled of the two legal advocates in the courtroom. She sneered at him and said, “What are you saying, she raped you, Mr. Smith?” Smith brushed off the attack. Later, about a second sexual encounter, she leered, “What are you, some kind of sex machine?”

Smith weathered the assault coolly. He reiterated his story that the evening had turned ugly when he had inadvertently called the accuser “Kathy.” She “sort of snapped…she got very upset.” Later, he said, Bowman apologized as she was leaving the compound, “I am very sorry I got upset. I had a wonderful night. You’re a terrific guy.” Minutes later, however, she was back, crying and complaining he had raped her, repeatedly calling him, “Michael”.

The closing arguments went much the same as the trial. Lasch called for justice and implored the jury to believe Bowman. She didn’t want the jury to let him, Smith, get away with it. Black approached with an ease and knowing. He assured the jury that what they were about to do was the right thing, he seemed to know that they had already decided, he had told them as much in his opening statement.

It took the jury 27 minutes to return with a not guilty verdict that surprised no one.

Court TV would go on to broadcast the trial of the Melendez brothers and eventually change everything with gavel to gavel coverage of the OJ Simpson trial, but for me it was the trial of William Kennedy Smith that would have some strange impact on my life. I was captivated by Roy Black. I don’t know if Smith raped Ms. Bowman or not, but I do know that Roy Black believed that he didn’t. He advocated for his client and at the same time had compassion for Patricia Bowman. He made it clear to the jury that he did not blame Bowman, but rather the prosecution for not vetting the false allegation. The stakes were real, it wasn’t a game it was real life, and these weren’t actors they were real people with real feelings.

I found myself in a similar situation than that of Mr. Black last September when I had the honor of representing Michael Tadlock in a Pittsburg County courtroom. It was not Roy Black, but my law partner, Blake Lynch, that cross-examined the accuser in a similar fashion. We attacked the system that had failed both the accused and our client in an overzealous prosecution. The result was a favorable one, and I will forever feel that I had some small part in bringing the truth out into the light of day. I am, after all, a trial lawyer.

No Comments