05 Jul THE STORY OF “THE GREATEST” AND HIS GREATEST FIGHT

Cassius Marsellus CLAY, Jr. also known as Muhammad Ali, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES.

THE STORY OF “THE GREATEST” AND HIS GREATEST FIGHT

Cassius Marsellus Clay was born January 17, 1942 in Louisville, Kentucky. He would eventually go down in history as perhaps the greatest boxing champion of all time, but he will also be remembered as one of the greatest champions of the First Amendment.

On February 25, 1964, Clay fought Sonny Liston for the Heavyweight Championship in Miami. In a major upset, Liston refused to answer the bell in the seventh round. Twenty-four hours after the fight Clay announced to the world that he was no longer Cassius Clay, but Muhammad Ali. Ali was an anomaly in 1960s America, first of all he was a loud self-promoter in a profession in which the athlete was generally silent, second, he was outspoken about politics in America, something an athlete just didn’t do. Oh, he was a black man from the Jim Crow South, too.

Ali was a member of the of the Nation of Islam, a militant organization led by Elijah Muhammed, and other charismatic leaders such as Malcom X. The Nation of Islam’s stated goals are to improve the spiritual, mental, social, and economic condition of African Americans in the United States and all of humanity. The organization adopts the teachings of the Qur’an and the tenants of the Muslim religion. The organization also has a long history of controversial views and has been criticized as a hate organization and to this day is tracked by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

In 1964, Ali took the U.S. Armed Forced qualifying test, but failed because his writing and spelling skills were sub-standard. The War in Vietnam continued to escalate and as more and more Americans lost their lives tests standards were lowered in 1965, and Ali was reclassified 1-A in February 1966. This reclassification meant that Ali was eligible for draft and induction into the U.S. Army. When Ali was notified of his status, he declared that he would not serve in the U.S. Army and considered himself a conscientious objector. In true Ali form, he spoke out loudly and controversially about his draft status. Ali couldn’t leave it at just his religious beliefs he criticized not only the war, but social politics as well. Ali famously said, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong … They never called me nigger.”

Ali may be perhaps the most famous person to claim to be a conscientious objector, but he certainly wasn’t the first. The conscientious objector status in America goes all the way back to the Revolutionary War. Exemptions varied by state, most states such as Pennsylvania, required objectors to pay a fine roughly equal to the time they would have spent in jail. Quakers who refused this extra tax had their property confiscated.

The first conscription in the United States came with the Civil War. Although conscientious objection was not part of the draft law, individuals could provide a substitute or pay $300 to hire one. By 1864 the draft act allowed the $300 to be paid for the benefit of sick and wounded soldiers. Conscientious objectors in Confederate States initially had few options. Responses included moving to northern states, hiding in the mountains, joining the army but refusing to use a weapon, or being imprisoned. Between late 1862 and 1864 a payment of $500 into the public treasury exempted conscientious objectors from Confederate military duty.

In the United States during World War I, conscientious objectors were permitted to serve in noncombatant military roles. About 2000 absolute conscientious objectors refused to cooperate in any way with the military. These men were imprisoned in military facilities such as Fort Lewis (Washington), Alcatraz Island (California) and Fort Leavenworth (Kansas). Some were subjected to treatment such as short rations, solitary confinement and physical abuse severe enough as to cause the deaths of two Hutterite draftees.

During World War II, all registrants were sent a questionnaire covering basic facts about their identification, physical condition, history and also provided a checkoff to indicate opposition to military service because of religious training or belief. Men marking the latter option received a detailed form in which they had to explain the basis for their objection.

By 1966, the test to qualify for conscientious objector status required satisfying three prongs. First, [He] must show that he is conscientiously opposed to war in any form; Second, [He] must show that this opposition is based upon religious training and belief must show that this objection is sincere; Finally, [He] must show that this objection is sincere.

Ali’s local draft board in Louisville, Kentucky, rejected his application for conscientious objector classification, and he subsequently appealed. The Justice Department, in response to the State Appeal Board’s referral for an advisory recommendation, concluded, contrary to a hearing officer’s recommendation, that Ali’s claim should be denied, and wrote that board that Ali did not meet any of the three basic tests for conscientious objector status. The Appeal Board then denied Ali’s claim, but without stating its reasons.

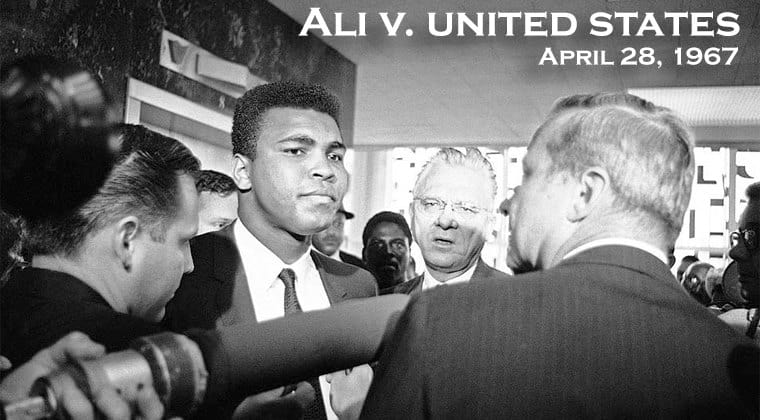

In early 1967, Ali changed his legal residence to Houston, Texas, where his appeal to be reclassified as a Muslim minister was denied 4-0 by the federal judicial district on February 20. He appeared for his scheduled induction into the U.S. Armed Forces on in Houston on April 28. As expected, Ali refused three times to step forward at the call of his name. An officer warned him he was committing a felony punishable by five years in prison and a fine of $10,000. Once more, Ali refused to budge when his name was called. As a result, on that same day, the New York State Athletic Commission suspended his boxing license and the World Boxing Association stripped him of his title. Other boxing commissions followed suit. He was indicted by a federal grand jury on May 8 and convicted in Houston on June 20. The trial jury was composed of six men and six women, all of whom were white. The Court of Appeals affirmed and denied the appeal on May 6, 1968.

In 1971, the case was taken up by the Supreme Court in Clay v. United States. Justice Thurgood Marshall recused himself because he was serving as Solicitor General when the case had began, and believed there to be a conflict, that left eight justices to decide Ali’s fate. The initial vote of the Justices was 5-3 to uphold Ali’s conviction and send him to jail. Justice Harlan was given the task of writing the majority opinion. After the vote one of Harlan’s law clerks gave him The Autobiography of Malcom X, and Harlan changed his mind about Ali. Harlan shocked the other Justices when he changed his vote and now the tally stood at 4-4. However, Harlan changing his vote would not be a victory for Ali, a 4-4 deadlock would have resulted in no opinion and Ali being jailed, and since no opinions are published for deadlocked decisions, he would have never known why he had lost.

Justice Potter Stewart proposed a compromise that would reverse Ali’s conviction on a technical error, and this eventually gained the assent of all eight justices and a unanimous decision to reverse. The Court claimed that by providing no reason for their conclusion that Ali had failed to meet requirements for conscientious objector status, the board had failed to properly deny Ali’s claim.

Ali was free from jail, but not from the ire of the American public, he became a controversial and derisive figure, and this played out to the entire world when he agreed to fight Joe Frazier in 1971. Named the “Fight of the Century”, it was set to take place in Madison Square Garden on March 8, 1971. Frazier was the recognized heavyweight champion of the world and undefeated as a professional. Ali, also undefeated, had been stripped of his championship due to his objection to serve. Ali portrayed Frazier as a “dumb tool of the white establishment”, “Uncle Tom”, and said the only people rooting for Frazier were member of the Ku Klux Klan. Ali again divided the nation and used his words to over emphasize the politics of the day.

The fight truly did live up to its billing and the two men fought perhaps the greatest boxing match of their individual careers. In the end Ali lost as a result of a unanimous decision, only to come back and complete a career that would include winning the heavy weight championship and being recognized universally as one of the greatest professional boxers of all time.

FREEDOM OF SPEECH

“They’re all afraid of me because

I speak the truth that can set men free.”

— Muhammad Ali

When most Americans think of the First Amendment, they think of freedom of speech. The late Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall eloquently captured the spirit of the First Amendment when he wrote in Police Dept. of City of Chicago v. Mosley (1972) that “above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content.” Another fundamental First Amendment principle is that the government may not restrict speech on the basis of viewpoint.

The story of Muhammad Ali is not so much important because of the things he said. For the most part many of the things he said over the course of his public life were hurtful, and mean, and in many accounts unfair. But, many things in the 1960s were unfair, especially in regard to the treatment of blacks. Muhammad Ali faced abject viewpoint discrimination at the hands of the federal government for his anti-war speech. Many say the government selectively prosecuted him because he was a proud black man in the Black Muslims who defiantly spoke his mind. So although the technical charge against Ali involved draft evasion and whether he was truly a conscientious objector, many believe the real reason was that he was an outspoken African-American who questioned U.S. policy and thumbed his nose at draft laws. And that is what this is all about.

The First Amendment protects a great deal of even offensive expression. Justice William Brennan expressed this concept well when he wrote in Texas v. Johnson (1989): “If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because it finds it offensive or disagreeable.” The First Amendment is a catalyst for disagreement and debate. Disagreement and debate have been the cornerstone of what drives all three branches of our governmental system, the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

It is important to remember that our Constitution is built on the belief that Government is not absolute, but rather the people are, and that the Constitution is a list of enumerated powers of the government, not the people. Speech is absolute, and can only be restricted by the government in certain instances. In 1789 the people of France overthrew a King, and in 1791 drafted a Constitution as well. Since that time they have had 13 Constitutions, 3 Charters, and are currently in their Fifth Republic. One could argue that this is the result of not understanding the role of the individual citizen first, before the powers of the government.

Thank god for men like Muhammad Ali, who may have said terrible things, overstated and exaggerated, and acted in ways many could argue as un-American. The fact is he acted as American as apple pie, he spoke his beliefs and he faced a government that was desiring to oppress him. You don’t have to like him or the things he said, (I for one disagree with many of the things he said) but you have to respect him for standing steadfast in his right to speak and that’s as American as you can get.

No Comments