13 Jun THE “LITTLE LINDBERGH LAW” AND THE STORY OF OKLAHOMAN, ARTHUR GOOCH

THE “LITTLE LINDBERGH LAW” AND THE STORY OF OKLAHOMAN, ARTHUR GOOCH.

The 1920s were nicknamed “the roaring twenties” for a reason. Americans were feeling good on the heels of victory in the WWI, and this ushered in a time of self-indulgence and pleasure. Women cut their hair, wore makeup, shortened their skirts, and demanded more independence. Hollywood began producing movies in the Twenties that exploited and emphasized sex. This was true in Oklahoma just as it was everywhere else in the country. However, the end of this glorious decade was far different than the beginning.

On October 29, 1929 the stock market crashed. It was followed shortly thereafter by the great depression, and Oklahoma experienced a great drought, and perhaps became the state most affected by the depression of the 1930s. Oklahoma was a state dependent on oil and agriculture. During the 1920s it experienced a tremendous boom. Farmers were were harvesting abundant fields, and oil barons were common place. But, when the stock market crashed and the fields dried up, Oklahoma came to epitomize the true cost of The Great Depression.

Over 60,000 Oklahomans migrated west in search of, well anything, behind them only dust. A drought that began in 1931 only worsened over the next five years, and that, combined with strong winds, poor farming techniques, and over grazing by cattle, created the Dust Bowl. The first black blizzard occurred on September 14, 1930, and 1934 saw fifty-six storms destroy lives, crops, and the landscape. Doctors and hospitals began reporting cases of a strange sickness, leading to a number of deaths, and later termed dust pneumonia. A myriad of citizens were sick and starving. People begged for, stole, or went without food, ate out of garbage cans, or fed road kill to their children. Often, family members took turns eating because there just was not enough money or enough food.

The 30s brought with it something else besides The Great Depression, a great crime wave. The indulgence of the 20s and hard, sharp decline of the 30s led to a new figure in American counter culture, the gangster. Oklahoma was riddled with robberies, violence, and kidnappings in the 1930s and “Boomtowns” continued to be pockets of criminal activity. Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd was the product of such an environment. Born in Georgia in 1904, he and his family moved to Oklahoma in 1911, and Floyd soon mixed with the wrong crowd. He committed his first holdup in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1925, and, during the 30s, Floyd robbed more than fifteen banks in Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio, and Mississippi, as well as his adopted state.

Kidnapping was on the rise as well. With the development of automobiles, kidnappers could abduct members of wealthy families and easily escape across state lines. The FBI was literally in its infancy and crossing a state line was a fast and sure way to avoid prosecution and create jurisdictional chaos. In 1931, the police reported upwards of 300 kidnappings, and the number continued to rise. St. Louis suffered a rash of kidnappings in and in 1931 Missouri Congressmen began to call on their colleagues for federal intervention. They asked that kidnapping be a federal crime, to combat the border crossing criminals. Their voices were heard, but it wasn’t a national interest until March 1932.

On March 1, 1932, the entire nation collectively gasped in horror. On the morning of that day it was discovered that Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., the infant son of “America’s Golden Boy”, was missing from his crib. The “Crime of the Century” as the papers across the country called it, had occurred. An outpouring of national sympathy and anger rang out and filled the halls of congress from horrified constituents. Senator John J. McNaboe of New York declared, “At no time in the history of the world has a crime shocked mankind as has the kidnapping of the baby of Colonel Lindbergh. Every family feels as though its own child has been suddenly snatched away. The kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby drove home to me the need for a law to curb such happenings.”

Unfortunately Baby Lindbergh was eventually found dead. Bruno Hauptman (there is a debate today as to his innocence) was convicted as a result of questionable handwriting analysis and executed. But, the federal government, reacting to the outcry of the public, eventually enacted a federal law that made kidnapping punishable by death, even in the event that the victim suffered no physical harm. This became known as the “Little Lindbergh Law”.

THE CRIMINAL LIFE OF ARTHUR GOOCH

Arthur Gooch grew up in Okmulgee during the prosperous 1920s, but his life was anything but easy. He lost his father, James Edward Gooch, at the age of eight,and his mother, Adella Ussery-Gooch, could neither read nor write and worked menial jobs. Named for a paternal uncle, his family called him “Little Arthur,” but, after the death of his father, the closeness with many of his relatives diminished. By 1920, Adella was forty-four years old, had buried her husband and three of her seven children, and taken in her widowed brother and his son and two daughters. While Oklahoma and the country flourished, they lived in extreme poverty. At the age of seven, the blue-eyed, black-haired Gooch peddled apples on the streets of Okmulgee and began stealing to help care for his mother. In 1923, at the age of fifteen, Gooch dropped out of school to find work, having only progressed to the sixth grade. Left without a father and little money, Gooch‟s life deteriorated from desperate to criminal.

By the mid-1920s, Gooch found work at a local grocery store and was the sole supporter of his mother. Working in the butchery, he became acquainted with a fellow employee, Mary Lawrence, and they married in 1927. Happy and content, the couple was soon expecting a baby, but, after the birth of their son Billy Joe, Mary quit

her job, and family life changed. The two started quarreling, and Gooch dreaded going home after work. Soon, he passed the nights, drinking and carousing. On September 25, 1930, when his son was only one month old, the Okmulgee police arrested Gooch for forgery, later dismissing the charge. In July of the following year, he, now unemployed, and four other men, Jesse Bohein, Charles Banks, G.E. Green, and Willie Carter, were arrested for stealing and stripping two cars; one vehicle belonged to A.D. Adcock, an oilfield worker, and the other to Deputy Sheriff Harry

DeVinne. Presented before Judge Mark L. Bozarth, Gooch and George Green pled guilty to grand larceny and received a sentence of eighteen months in the McAlester state penitentiary. After serving eleven months, Gooch was released on June 7, 1932,

but before long he saw the inside of a jail cell again.

By 1934, the Okmulgee police knew his name well, and, when a crime was committed, Gooch‟s name made their list of

suspects. Gooch teamed up with some other men and held up stores farmers around the Stuart and Calvin areas. He and his gang would kidnap their victims and leave them unharmed when it was no longer necessary to keep them.

On October 24, 1934, Gooch, and three other men escaped from a prison in Holdenville. They robbed and kidnapped their way from Holdenville to Henryetta to Choctaw. By November 7th two of the members of the gang had been captured, leaving Arthur Gooch and Ambrose Nix to hold up a gas station in Tuskahoma. The men decided to turn south, dumped their car in Durant stole another, and upon entering Tyler, Texas on November 25th, held up another gas station and tying the owner and an employee to a tree.

On Novenmber 26, the duo committed a crime that would eventually lead to the demise of Arthur Gooch. While driving though Paris, Texas, the two men had a flat tire in the early morning hours and sought out an auto repair shop. Policemen R.N. Baker and H.R. Marks drove by in their patrol car, noticed the vehicle, and became suspicious, thinking the two men could possibly be part of the Bonnie and Clyde gang. The officers stopped, approached Gooch, and asked to see the title papers of the car. Gooch stated he did not have them, and Marks and Baker surrounded him. Gooch reached for his gun, and he and Marks struggled. When Baker started to draw his gun, Nix yelled, ‟Hands up!‟ Nix approached Baker and shoved him into a glass

showcase; the glass broke and a piece cut Baker‟s left hip. Meanwhile, Gooch had relieved Marks of his firearm, and the two fugitives forced the officers into the back seat of their patrol vehicle. With Nix holding a gun on the policemen, Gooch retrieved money, three shotguns, two rifles, and four pistols from their stolen car and

rejoined Nix. Gooch then held a firearm on Baker and Marks, and Nix began driving north. Avoiding any major highways, the group crossed the state lines and entered Choctaw County, Oklahoma, and then Pushmataha County. Around 9:00 p.m. on the night of November 27, 1934, forty-two hours since the kidnapping, Gooch and Nix released the officers in the Kiamichi Mountain area between Cloudy and Snow. Gooch dressed Baker’s wound before releasing the officers, and the fugitives were not seen again until late December.

Gooch was eventually arrested just outside of Okemah, when officers stopped the car he was riding in. Nix was shot and killed during the arrest and Gooch was placed in the Okfuskee County Jail.

Gooch was sent to Muskogee and charged, on December 26, with violating the Dyer Act (theft of an automobile) and the Federal Kidnapping Act. However, on May 30, 1935, he was indicted for “kidnapping and injury by force.” Arraigned the following day before Eastern District Court Judge Robert Lee Williams, a former Oklahoma governor and Oklahoma Supreme Court judge, Gooch entered a plea of not guilty through his lawyer, E.M. Frye, a former assistant district attorney who had been assigned Gooch’s case, but, less than two weeks later, he withdrew his plea and pled guilty. Known for his “hard bitten reputation” and “mortal hatred of dishonesty,” Judge Williams denied his guilty plea, stating the issue would be presented before a jury. By the magistrate’s orders, the newly amended Lindbergh Law was scheduled to have its first test on June 10.

June 10, 1935, Arthur Gooch’s day in court, arrived, and he again requested to plead guilty to the charges lodged against him, kidnapping of two Texas police officers and injuring one of them. Judge Williams repeated his previous denial “because a life sentence was the maximum he could give without a jury verdict.” The amended Lindbergh Law stated that a defendant “shall, upon conviction, be punished by death if the verdict of the jury shall so recommend, provided that the sentence of death shall not be imposed by the court if, prior to its imposition, the kidnapped person has been liberated unharmed.” Since Baker had received a cut during the struggle with Nix, Gooch faced the possibility of execution, if tried before a jury and found guilty. Though he did not inflict the wound upon the officer,even though he had not been the one to inflict the wound.

Gooch was tried and the jury deliberated only to stop to ask questions of the court regarding their duty to impose death. The judge answered their questions, and after several hours of deliberation the jury returned to the courtroom. Foreman Dial Currin read the verdict: “We the jury…duly impaneled and sworn, upon our oaths, find the defendant Arthur Gooch guilty, as charged in the first count of the indictment [kidnapping]. We further find the

defendant guilty, as charged in the second count of the indictment [injury by force], and we recommend that he be punished by death.”

Gooch’s attorney immediately moved for a new trial and the matter was set for hearing. At the hearing Judge Williams overruled the motion and stated, “It is now by the court here considered, ordered and adjudged that the said defendant, Arthur Gooch, for the crime by him committed, shall on September 13, 1935, be hanged by the neck at the Muskogee jail until dead.” The judge asked the defendant, whose wife and son were in attendance, if he had anything to say. Gooch replied, “I think there have been worse crimes than mine and I don‟t see why I should hang.” Tending to be harsher on repeat offenders, Williams responded by stating that “other juries have been cowardly,” and it was “no pleasure for me to sentence a man to die but when they roam about the country like a pack of mad dogs, killing and robbing and kidnapping, I am going to do it.”

Arthur Gooch was sent to “Death Row” at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester, Oklahoma. From there he began appeals to attempt to save his life. His appeals went all the way to the Supreme Court, but only to have his conviction and sentence affirmed.

On April 3rd, 1936, while Gooch was sitting in a jail cell in McAlester awaiting answers on his appeals, Bruno Richard Hauptman was executed in New Jersey for the death of Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. His appeals exhausted Gooch was summoned once again to stand before Judge Williams in Muskogee on May 7th.

The magistrate then sentenced Gooch, a “two-time loser,” to be hanged at the state penitentiary on June 19. Williams asked if Gooch had anything to say, and he replied, “I didn’t commit a crime for which I should be executed. I admit my life hasn’t been what it should have been, but I don’t think I should die.‟ The judge responded by advising him to “make peace with your God.”

Many members of the public began to speak openly that execution seemed to be to harsh of a punishment for Gooch. However both President Roosevelt and Governor Marland refused to intervene. Mabel Basset, the State Commissioner of Charities and Corrections led the charge to free Gooch from the gallows, but even her influence failed to save Arthur Gooch.

Rich Owens agreed to be Gooch’s executioner, but he had never hanged anyone. In 1915, Owens built Oklahoma’s first electric chair, known as “Old Sparky,” and, when his career ended, he had electrocuted sixty-five but only hanged one. He took his work seriously, but executing people did not bother him “anymore than jerking a chicken‟s head off.‟ When told that Gooch was to die

on the gallows, Owens was disappointed his electric chair would not be used, believing hangings took too long and were messy.

The day of the execution, June 19, 1936, arrived. A gallows had been erected, and the officials decided to have a public hanging, adhering to the belief that “Executions are intended to draw spectators. If they do not draw spectators they don‟t answer their purpose.” The publicity of the death was intended to deter future

criminals by exposing the consequences of breaking the law. Gooch sent his mother a telegram that said, “President turned me down. Go live with sister. Goodbye to all,‟ and, at 5:00 a.m., Gooch, led by Deputy Warden Jess Dunn, emerged from the

jail and walked across the prison grounds to the gallows, Gooch ascended the scaffold’s steps to the awaiting Rich Owens.

When asked if he had any last words, Gooch merely wanted to know where he needed to stand. Before the 200 witnesses, Owens slipped the hangman’s knot over Gooch’s head, covered him with a black hood that reached his waist, and pulled the trap door’s trigger. Gooch fell through the hole, the knot slipped up behind his ears, and he began to strangle. It took 26 minutes for Gooch to die, many spectators were revolted at the sight of Gooch’s slow tormented death.

The doctors finally pronounced him dead, and his body was removed. Immediately, Assistant Deputy Warden John Russell called to have the gallows disassembled and the rope cut up for souvenirs, but Owens asked to keep the noose and the knot. When questioned on the length of time it took for Gooch‟s heart to stop beating, Owens answered, “You pull a chicken’s head off and

he flops around like everything. That’s the way it was with Gooch. He just had to have time to die.”

Gooch’s horrific public execution led to change. The last public execution occurred later that year in Galena, Missouri, and the death amendment to the Lindbergh Law was eventually removed. Gooch was the only man to have ever been convicted under the Lindbergh Law and hanged in accordance with its controversial amendment.

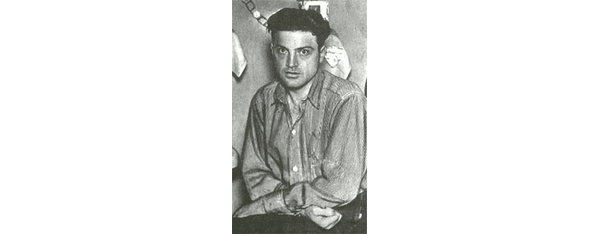

An original newspaper picture of Arthur Gooch hangs in the lobby of our office, and I walk by it nearly every day. Sometimes I wonder what I would have felt about Arthur Gooch. Woould I have petitioned for his clemency, or championed his punishment? If I was standing in that courtyard watching him jerk at the end of that rope, would I have been revolted, or fought my way to the front of the crowd to claim my souvenir? I like to think I would have not been swept up in the fervor of the masses at the time, but who knows, being part of the crowd, getting swept up in the passion of the majority, seems to always be easier path.

No Comments