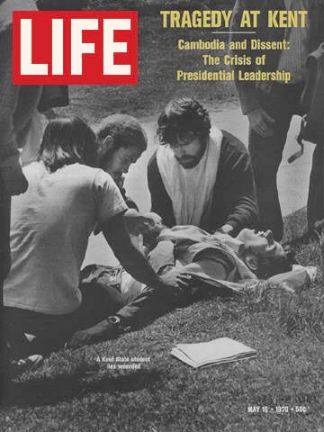

05 May THE KENT STATE MASSACRE – 45 YEARS LATER PART III

THE KENT STATE MASSACRE – 45 YEARS LATER

PART III

THE AFTERMATH

After May 4, 1970 campuses across the united states had their own student strikes, and some led to more violent clashes with police and government officials. The nation divided sharply, and chose very different sides. The anti-war movement declared the shooting at Kent State a massacre and an example of a government trying to eradicate citizens constitutional rights and even their lives. The “silent majority”, as named by President Nixon, began to become vocal. Some people publically denounced the actions of the students and criticized the Guard for not “shooting more.”

In one of the most ironic moments in American history, an American public who wanted to collectively end a foreign war, began to war with each other at home. To say the mood was tense was an understatement. Protestors would take to the streets carrying signs, burning the President in effigy, and desecrating the flag. In turn, as occurred in New York, union members greeted protestors with fists and bats in what they concluded was support of the President’s policies.

A series of federal, state and local investigations and legal battles occurred after the shooting at Kent State. Eight Guardsmen were indicted as well as twenty-five students and faculty members in response to the events of May 1-4. The guardsmen were not acquitted, and the students and faculty, called the “Kent 25”, of the 25, one was convicted for interfering with a fireman, two pleaded guilty, one was acquitted, and the others had their charges dismissed for lack of evidence.

Although some guard members and officials made claims that the firing came after some reported “sniper” fire, no investigative body found any evidence to support such a claim. The FBI’s investigation eventually concluded: There was no sniper; the Guardsmen had not been surrounded; They (Guardsmen) could have resorted to tear gas, rather than shooting; the rock throwing had not been as widespread or dangerous as reported by General Canterbury; and the shooting was “not proper and not in order”.

Civil suits also followed the tragic events at Kent State. A guardsman filed a libel suit, and families of those killed and injured filed suit against the university and government. The suit of the families was initially dismissed on grounds of immunity, however a 1974 8-0 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in Scheuer vs. Rhodes, reversed the lower court’s decision and said that the defendants could not claim immunity. Justice Douglas di not take part in the ruling.

Eventually, an out-of-court settlement is reached and the for $675,000.

NIXON’S STRANGE MORNING AT THE LINCOLN MEMORIAL

At 3 p.m. on May 4, 1970, White House chief of staff H. R. Haldeman informs President Nixon of the shootings of four unarmed college students by National Guardsmen at Kent State University in Ohio. Nixon is initially aghast at the news. “Is this because of me, because of Cambodia?” he asks. “How do we turn this stuff off?… I hope they provoked it.”

To say that the president was shocked at what had occurred at Kent State would be an understatement. But what he did on morning of May 9th, seemed downright bizarre. After finishing a press conference at 10 p.m. on May 8 during which he faced tough questions about his decision to invade Cambodia and the campus furor it provoked, Nixon says he then fielded about 20 telephone calls “from VIPs,” went to bed at 2:15 a.m. and “slept soundly” until shortly after 4 a.m.

Nixon says he woke up shortly after 4 a.m., went into the Lincoln sitting room, and began listening to a record of Eugene Ormandy conducting a Rachmaninoff piece. (Several already-released tapes of Nixon phone conversations feature classical music blaring in the background at rock n’ roll volume.) The loud music awakened White House valet Manolo Sanchez, and as Nixon looked out the window at a small knot of people gathering outside on the National Mall, he asked his valet if he had had ever been to the Lincoln Memorial at night. When Sanchez replied no, Nixon impulsively told him, “Get your clothes on, we’ll go down to the Lincoln Memorial!”

While the President was pointing out the inscriptions on the walls of the Memorial to his valet, a handful of student gathered there noticed the strange visitor. Students came up to the President and they began to engage in an often rambling and unstructured discussion of everything from the war to pollution.

When the discussion turned to Vietnam, Nixon says he told the students, “I hope that (your) hatred of the war, which I could well understand, would not turn into a bitter hatred of our whole system, our country and everything that it stood for. I said that I know probably most of you think I’m an SOB. But I want you to know that I understand just how you feel.”

As quietly as he arrived he left. In the months and years to follow the President publically criticized the student protestors harshly and rode a waive of support into a second term winning an overwhelming 49 state victory.

CONCLUSION

Opinions were made on May 5th, 1970. Most people in America made a decision on which side of the road they found themselves in a very divided America. The Kent State shootings simply urged those who were sitting on the fence to promptly pick a side upon which to land. The divisions and lines that were drawn that day remained for many years, however they did eventually began to fade. Terrible tragedies tend to produce valuable lessons, and I believe that lessons are still left to be harvested from what happened on the campus of Kent State University on May 4, 1970.

No Comments