03 May THE KENT STATE MASSACRE- 45 YEARS LATER

THE KENT STATE MASSACRE- 45 YEARS LATER

This may 4th will mark the 45th anniversary of the shooting of four unarmed students on the campus of Kent State University. On that fateful day National Guardsmen fired 67 rounds over a period of 13 seconds, killing four students and wounding nine others, one of whom suffered permanent paralysis.

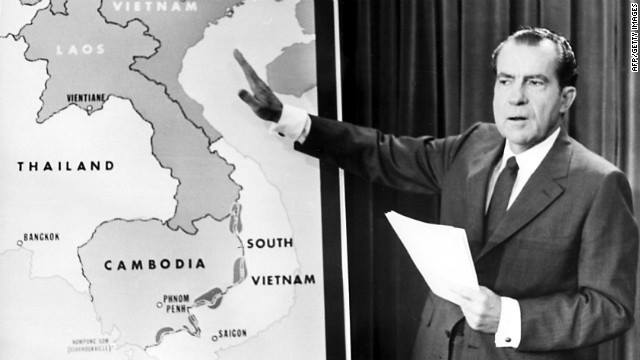

NIXON, VIETNAM, AND THE INVASION OF CAMBODIA

In 1968 Richard Millhouse Nixon was elected to the office of the President of the United States. He was elected in large part on his promise to end the war in Vietnam. From 1968 throughout 1969, American forces continued to be mired in war in Southeast Asia. The military gains seemed to continue to appear minimal at best, and protests at home grew to record numbers. A widening gap began to grow between young people and the working and older generation.

Although the war seemed to winding down no real end or victory seemed to be in sight. On April 30, 1970, President Nixon spoke to the American people on television and radio. He announced that American forces would be invading the neighboring country of Cambodia. Nixon, and his military advisers, believed that by invading Cambodia, they would be able to attack the headquarters of the Viet Cong, which had been using the country as a sanctuary. Nixon legitimately believed that this invasion would break the back of the enemy, end the war in Vietnam, and fulfill his campaign promise. What his advisers had not calculated was the impact his decision would have on the homeland.

The Vietnam War also known as the Second Indochina War, was a Cold-War era proxy war. The war actually began on the 1st of November, 1955, and was fought between the North and South Vietnamese. The North was supported by supported by the U.S.S.R, China, and other communist allies; the South was supported by the United States and other anti-communist allies.

The U.S. government viewed American involvement in the war as a way to prevent a Communist takeover of South Vietnam. This was part of a wider containment strategy, with the stated aim of stopping the spread of communism. According to the U.S. domino theory, if one state went Communist, other states in the region would follow, and U.S. policy thus held that Communist rule over all of Vietnam was unacceptable. The North Vietnamese government and the Viet Cong were fighting to reunify Vietnam under communist rule. They viewed the conflict as a colonial war, fought initially against forces from France and then America, as France was backed by the U.S., and later against South Vietnam, which it regarded as a U.S. puppet state.

The war escalated in the 1960s, most notably in 1968 when the communist forces launched the Tet Offensive. The Tet offensive was designed to blitz the American forces when they would have least expected it. Although it failed in its goal of overthrowing the South Vietnamese government, it became a true turning point in the support of the war in the United States.

Of the Tet Offensive, Walter Cronkite said in an editorial, “To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To suggest we are on the edge of defeat is to yield to unreasonable pessimism. To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion.”

Young people, particularly college students across the country began to protest the war with vigor. As the gap between the protesters and, what Nixon coined the “silent majority” (those Americans that he said supported the war without showing it in public) continued to widen, the protesters themselves, ironically, became more militant. This period gave rise to such groups as the “Weathermen”, who deployed bombs on American businesses and buildings as a so-called form of protest. Different factions and groups began to merge into a common goal of protest against the war, and the front lines of this protest was found on college campuses from Berkeley to Harvard.

STUDENTS RESPOND TO THE PRESIDENT’S ADDRESS

On May 1, 1970, protests occurred on college campuses across the country in response to the President’s address the previous day. At Kent State University, an anti-war rally was held at noon on the Commons, a large, grassy area in the middle of campus which had traditionally been the site for various types of rallies and demonstrations. Fiery speeches against the war and the Nixon administration were given, a copy of the Constitution was buried to symbolize the murder of the Constitution because Congress had never declared war, and another rally was called for noon on Monday, May 4.

That evening in downtown Kent began peacefully with the usual socializing in the bars, but events quickly escalated into a violent confrontation between protesters and local police. The exact causes of the disturbance are still the subject of debate, but bonfires were built in the streets of downtown Kent, cars were stopped, police cars were hit with bottles, and some store windows were broken. The entire Kent police force was called to duty as well as officers from the county and surrounding communities. Kent Mayor Leroy Satrom declared a state of emergency, called Governor James Rhodes’ office to seek assistance, and ordered all of the bars closed. The decision to close the bars early increased the size of the angry crowd. Police eventually succeeded in using tear gas to disperse the crowd from downtown, forcing them to move several blocks back to the campus.

The next day, Saturday, May 2, Mayor Satrom met with other city officials and a representative of the Ohio National Guard who had been dispatched to Kent. Mayor Satrom then made the decision to ask Governor Rhodes to send the Ohio National Guard to Kent. The mayor feared further disturbances in Kent based upon the events of the previous evening, but more disturbing to the mayor were threats that had been made to downtown businesses and city officials as well as rumors that radical revolutionaries were in Kent to destroy the city and the university. Satrom was fearful that local forces would be inadequate to meet the potential disturbances, and thus about 5 p.m. he called the Governor’s office to make an official request for assistance from the Ohio National Guard.

Members of the Ohio National Guard were already on duty in Northeast Ohio, and thus they were able to be mobilized quickly to move to Kent. As the Guard arrived in Kent at about 10 p.m., they encountered a tumultuous scene. The wooden ROTC building adjacent to the Commons was ablaze and would eventually burn to the ground that evening, with well over 1000 demonstrators surrounding the building. Controversy continues to exist regarding who was responsible for setting fire to the ROTC building, but radical protesters were assumed to be responsible because of their actions in interfering with the efforts of firemen to extinguish the fire as well as cheering the burning of the building. Confrontations between Guardsmen and demonstrators continued into the night, with tear gas filling the campus and numerous arrests being made.

Sunday, May 3rd was a day filled with contrasts. Nearly 1000 Ohio National Guardsmen occupied the campus, making it appear like a military war zone. The day was warm and sunny, however, and students frequently talked amicably with Guardsmen. Ohio Governor James Rhodes flew to Kent on Sunday morning, and his mood was anything but calm. During a press conference at the Kent firehouse, an emotional Governor Rhodes pounded on the desk and called the student protesters un-American, referring to them as revolutionaries set on destroying higher education in Ohio. “We’ve seen here at the city of Kent especially, probably the most vicious form of campus oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups. They make definite plans of burning, destroying, and throwing rocks at police, and at the National Guard and the Highway Patrol. This is when we’re going to use every part of the law enforcement agency of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. We are going to eradicate the problem. We’re not going to treat the symptoms. And these people just move from one campus to the other and terrorize the community. They’re worse than the brown shirts and the communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes”, Rhodes said. “They’re the worst type of people that we harbor in America. Now I want to say this. They are not going to take over campus. I think that we’re up against the strongest, well-trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.” The widespread assumption among both Guard and University officials was that a state of martial law was being declared in which control of the campus resided with the Guard rather than University leaders and all rallies were banned. Further confrontations between protesters and guardsmen occurred Sunday evening, and once again rocks, tear gas, and arrests characterized a tense campus.

In Part Two…the shooting on May 4th.

No Comments