01 Dec TULIA TEXAS: A STORY OF INJUSTICE, AND MASS INCARCERATION

TULIA TEXAS: A STORY OF INJUSTICE, AND MASS INCARCERATION

PART TWO-RIGHT HERE IN RIVER CITY

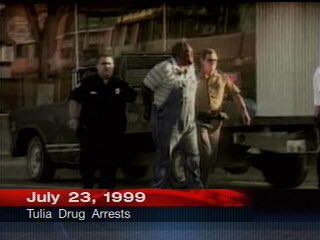

July 23, 1999, would turn out to be a day that would haunt the town of Tulia, Texas, and cast it into a statewide and even national spotlight. Overnight the word had gotten out and by the early morning the population of law enforcement officers multiplied to the incomprehensible. Actual newS cameras and reporters found themselves in Tulia, and this time it wasn’t to do a puff piece on a prize-winning hog, or a pie supper charity drive.

On the same main street that usually hosted the Swisher County Picnic Parade each July, now a very different mood hung in the air. One by one, 47 people marched before the cameras and reporters, all but six had black faces, and all of them had their hands restrained behind their backs. The press and curious parade-goers, that began to gather in front of the Swisher County Jail, were witnessing one of the largest round-ups of drug dealers in Texas history, and it would become one of the greatest travesties of justice in Texas history.

The citizens of Tulia (who did not live in the black community, which just saw a 10% decrease in its population) voiced their support for the arrests. The Tulia Sentinel, the town paper, ran a headline announcing that the “garbage” was being cleaned up in Tulia. An editorial in the same paper, proclaimed support for Sheriff Stewart and the District Attorney for rounding up the “scumbags”. Before the sun went down on the hardpan Texas plain, the good residents of Tulia had made up their mind: They HAD a problem with people peddling drugs in their town, and now it was time to lock’em up and throw away the key.

Tom Coleman was afforded the status of hero. He had successfully shed the shadow of his Texas Ranger Father, and blazed his own trail in Texas law enforcement history. His was a story of Old West lore, a lone lawman riding into a troubled town, hearing the cries of help from its forlorn and righteous citizenry, isolating the bad doers and bringing justice, and not just any justice, good ‘ol Texas justice. Coleman was showered with praise, gifts, and recognition. Coleman was presented with “Lawman of the Year”, honors, and given a plaque at a ceremony from then State Attorney General, now Senator John Cornyn. Coleman’s rise from derelict to hero was rapid, but at the end of the day a prize winning Tulia hog, is still a hog, and its destiny is to be bacon, no matter how many prizes it wins.

THE TRIALS

The first trial was that of Joe Moore. The same Joe Moore that was touted as Tulia’s “Kingpin”. And the same Joe Moore that lived in a shack and drove a rusted out sedan. Joe insisted he was innocent, and that he had never sold cocaine to Tom Coleman. The state had no actual physical evidence, or corroborating evidence for that matter, only the description of events from Tom Coleman.

Moore went on trial accused of delivering two “eight balls” of cocaine to Coleman, and allegedly within 1,000 feet of a school. Moore had been previously convicted of two felonies from discretions in his youth and as a result faced the possibility of an enhanced sentence if convicted, but he put his faith in the judicial system and maintained his innocence. Joe Moore put his faith in the wrong place and was found guilty and sentenced to 99 years in prison.

Clearly a tone had been set by the folks of Swisher County that found themselves eligible for jury duty. They believed Tom Coleman, and they were going to finish taking out the garbage. The sentences that were being handed down were staggering. Even first time offenders like Freddie Brookins, 22, who was charged with one count of delivery, was found guilty and sentenced to twenty years. No physical or corroborating evidence was ever presented at any trial. The cocaine that was supposedly delivered was not present, and no other law enforcement officer, other than Coleman, claimed to have ever seen it.

As the trials progressed and persons claiming their innocence began to be led off to decades of incarceration, plea deals started to be made. Some of the accused opted to plead guilty and receive a determined amount of prison time that would allow them some hope of release, rather than risk trial and never see the outside of a penitentiary again.

One would think that Tom Coleman must have been a great witness, however the truth is quite the opposite. Coleman regularly got dates and times wrong on the stand, and as the trials went on some of his “recollections” became suspicious. Coleman recalled buying cocaine from a man, who later was able to produce time cards and witnesses that proved he was at work when the alleged sale occurred. On another occasion Coleman recalled buying an eight-ball from a woman, when it was later proven that she was in Oklahoma City cashing a check at the time. Coleman just brushed off the discrepancies by citing his unsophisticated record keeping process. Coleman didn’t keep a journal or notebook of his transactions, rather he claims he wrote them on his arm or leg at the time and then committed them to his steel trap Texas Lawman memory.

The prosecution protected their star witness’ memory problems by quietly dismissing those troublesome cases and therefore keeping his credibility issues from falling in the hands of defense counsel. The cases continued to wind their way through the court system, and some inside and outside of the community started to question the drug bust.

THE TIDE BEGINS TO TURN

An unlikely duo of Rev. Alan Bean and fouled-mouthed rancher, Gary Gardner began to ask questions. Bean and Gardner eventually joined forces and began to voice their concern that a possible injustice might be taking place. A sentiment began to grow, “How do you have 47 drug dealers in a town of 5,000? Who are they selling to, each other?” That along with the lack of any evidence or corroboration just didn’t seem right.

Bean started an organization called “Friends of Justice” and Gardner filed a writ of Habeas Corpus for his friend Joe Moore. Outsiders, including a reporter by the name of Nate Blakeslee, and groups like the NAACP began to question the drug bust as well. Slowly but surely the problems with the cases, and the star witness began to emerge.

Jeff Blackburn, an Amarillo criminal attorney, took notice as well. He entered several of the cases of convicted Tulia residents and began to file appeals on their behalf. His investigation would reveal that Coleman was a lawman with a tainted past and possibly an outright liar. Blackburn was able to lift the veil on those “troublesome cases” that prosecutors quietly dismissed, and began to build a case to free his clients.

Coleman’s rise to upper echelons of law enforcement hierarchy were short lived. He took on more assignments, but his natural inclination to being a louse revealed itself. He was fired in Ellis County after a claim of sexual harassment. Further, former employers started to discuss the top lawman’s work history and what they had concluded about his character.

THE SHOE DROPS

As the credibility of Tom Coleman continued to fall apart, and appellate courts began to take notice of the briefs and filings of Mr. Blackburn, slowly change began to occur for the convicted Tulians.

Coleman was indicted on perjury charges and would face a trial of his own. Thirty-five defendants were pardoned by Gov. Rick Perry on Aug. 22, 2003, and taxpayers in 17 of the counties that participated in the regional task force paid them about $5.9 million as part of a settlement. The defendants split about $4 million, and attorneys were paid the rest.

Housing the incarcerated defendants was estimated to have cost Swisher County residents about $230,000, which translated to a 5.8 percent increase in county property taxes, according to the county in 2000. In April 2003, the county also agreed to pay $250,000 to the defendants in exchange for immunity from civil lawsuits.

Among those pardoned was Joe Moore. Joe received over a quarter million dollars from the people who had put him in prison. He bought a used Ford Expedition that has carried dozens of black children to Friends of Justice sponsored events all over the panhandle. Then, with the kind assistance of Charles Kiker, a retired preacher and former real estate man, Joe bought a little hog farm. Joe would pass from heart disease in 2008.

Tom Coleman would go to trial for perjury and would also be found guilty. He wouldn’t serve any time in prison, but he would receive ten years of probation, a far cry from the years of imprisonment his victims had to endure. Coleman was last known to reside in Waxahatchie, where he tries to find work as a welder. He claims that he told the truth about all of the deals he made in Tulia, and stands by his story. “They were pissed off at me because all the blacks went to jail, and I was the cause of all this misery,” he says. “Well, I wouldn’t have been the cause of all this misery if they hadn’t sold me dope. I’m not an angel. I’ll own up to anything I didn’t do right, but I’ll sure as hell not own up to anything I didn’t do.”

One can assume that Coleman would disagree with the judge who presided over the convicted defendant’s appeals. He declared in his Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, that the prosecution had withheld critical impeachment material; that Coleman was the most devious, non-responsive law enforcement witness this Court has witnessed in 25 years on the bench in Texas; and that it would be a travesty of justice for the Tulia convictions to stand. One can assume.

CONCLUSION

Even if it was possible to change the past, I believe that the past is obdurate, and would resist any attempt at change. The present and the future, however are a different story. Tulia should be a story that every American knows. It is a story of not just inherent racism, government overreach, and the fallacy of the “War on Drugs”, but also a story of hope. It is hopeful in the sense that those who recognized injustice did something about it, and in the end (although slowly) the wheels of justice actually turned. Sure, a large amount of the citizens of Tulia did stick their heads in the sand. They buried their common sense, and fell into a trap laid by a smooth talking swindler. Tulia was just the “River City” of the “War on Drugs” warped version of the “Music Man”.

But, Tulia, much like the fictional “River City” left its citizenry and the audience with a message and a moral. What if anything will we take from Tulia?

(If you are interested in more information regarding Tulia, I would suggest “Tulia: Race, Cocaine, and Corruption in a Small Texas Town”, by Nate Blakeslee.)

No Comments