22 Jun BITTER FEUD : The Story of the Trial of Dale Robert Roland

PART II

WHAT DO I DO NOW?

I tried to forget about Dale Roland, but unfortunately the fact that his trial was only days away wouldn’t let me do that for long. A couple of days later I called another lawyer I knew and told the whole story. My friend first asked me if I even wanted to do this, because if I didn’t I shouldn’t, even Dale deserves more than that. I thought about it for a minute or two and responded that in fact I did want to do the trial. I tell myself all the time that this work is bigger than just me, and if I quit then I would have to live with the hypocrisy of my own rhetoric. My mind made up, we started talking about Dale. Who he was as a person?

Dale, now in his fifties had spent most of his life in prison. He started his career as little more than a petty thief and over time collected drug charges, and charges for assault eventually racking up more than ten felony convictions from Oklahoma to South Dakota. I had to confess that I didn’t really know Dale’s story, I would tend to tune him out when he began, in my opinion, rambling. I did conclude that he had clearly suffered some effects of mental illness, whether it was PTSD (common among those that have spent time in a penitentiary), or something else. He would send me long letters that spoke of elaborate conspiracy theories, mixed with biblical passages. His own family had long since disowned him and was currently pushing for his incarceration now. At one point, I even considered that Dale actually wanted to go back to prison.

After talking about it, I found a place in myself where I could view Dale sympathetically. I didn’t have to like him, but that didn’t mean I should abandon him either. Dale was just a kid when he first entered the criminal justice system, a poor kid that that was ate up and spit out by a system that feeds on people just like him. He was more a product of our system than anything, and if I could stand behind anything and fight, I could do it for that. I thanked my friend, and made a promise that I would fight for Dale, even if it meant he would fight me.

THE TRIAL

The first day of trial would only consist of picking a jury, what the court calls Voir Dire. Before the jurors arrived, I met with Dale in a room just off of the Courtroom. Joining me was my associate, Jared Snedden, I had tasked him with giving the opening statement. He was about to meet Dale for the first time, before delivering the opening the next day. Jared was noticeably nervous, this was his first jury trial ever, and on top of it I had told him about Dale’s temperament and volatile nature.

Dale came in wearing the gray button up shirt, slacks, and shoes, that my staff had purchased him from The Goodwill in McAlester. It had been more than 18 months since Dale had worn anything other than a starchy, jail issued, bright orange jump suit. He looked to be calm, maybe the clothes had made him feel just a little more human. We talked for about thirty minutes. We talked about his life mostly. At points he became agitated, but he did talk and he told me things that I needed to hear. He did make it clear that he did not like me, and although I was seeing Dale in a different a light, the feeling was mutual.

We went into the courtroom and waited for the potential jurors. They streamed in and took their seats. One by one they were called to the front until we had a total of 25 to choose from with the remainder continuing to sit in the gallery in the event some of the jurors might have to be excused.

The judge conducts the questioning first. Judge Fry asked the jurors to provide certain information that he is required to ask according to the law. Voir Dire can seem long and stale at times. The judge will exhaust all the preliminary matters, such as what the jurors do for a living, if they are married, whether they have family members that are in law enforcement, whether they have ever been charged with a crime, and so on. Assistant District Attorney Joe Watkins did the Voir Dire for the state, and it was typical as far as prosecution versions of Voir Dire go. He spent most of his time asking jurors if they could be fair and requesting that they swear allegiance to following the facts and the law, very hand over your heart kind of stuff. Aside from a couple of jurors having to be excused because they could not live up to this pledge, or felt they couldn’t. The whole affair was rather bland except for one moment of excitement.

One juror claimed that she had previously worked for the LeFlore County Sherriff’s department, but that she could set that aside and be fair. She promised that she wouldn’t let her associations with law enforcement prompt her to treat their testimony any differently. Then she said, “Wait, you said that officers from the DA Task for were going to testify?”

“Yes, ma’am I did,” Watkins replied.

“Is one of those officers Travis Salisbury?”

“No, ma’am, he is not called as a witness in this case.”

“Oh, ok then. Well I can be fair. I couldn’t if he was gonna testify, because he is a liar, and I wouldn’t believe anything he ever said.”

I chuckled to myself. The textbook on picking a jury tells you that you never keep people who have strong ties to law enforcement, but I’m not much of a follower of the textbook. I like to listen for people that feel, and I liked this lady, I wanted to know more about her.

After having the jury swear their allegiance for the umpteenth time about some legal nuance, the state finally passed the jury for cause and I was going to get to speak to them for the first time. I knew what I was going to say, and I knew that it would grab their attention right out of the gate.

“My name is Brecken Wagner and I am the attorney for Dale Roland. The gentleman seated there at the table next to my associate is Mr. Roland. Ladies and Gentlemen, I’m going to share with you something that I think you should know. I can’t stand Mr. Roland, and he doesn’t like me. Isn’t that right, Dale?”

“Yep,” Dale responded from across the room.

“As a matter of fact, the last time we were in court together he said some awful things to me and I said some pretty awful things back to him. I just can’t think of anything nice I can say about him at all, and I don’t like him even a little bit. How do you feel about hearing me say that?”

Some mouths were agape, some jurors bounced from looking at Dale and then back at me as if we were serving volleys to each other, some just looked at the floor. This was uncomfortable. This was strange. And they started talking.

We talked about lots of issues, including what they wanted to know so that they could make a decision. They spent a good deal of time discussing things among themselves, and they were very clear with me that they expected me to do my job and work to help my client. By the end I was pleased with all the things I had found out about these jurors and I felt comfortable with them moving forward.

Both the state and myself struck jurors until we arrived at a final twelve and an alternate. I was happy to see that the former county employee had made the cut.

After the jurors were allowed to go, Judge Fry asked if there was anything else before we adjourned for the day. Dale asked to speak. He again noted his frustration that the judge had insisted that I would represent him. He said he would rather represent himself and that I “wasn’t no good”. He also threatened that he might cause a scene and therefore a mistrial. Judge Fry listened patiently, encouraged him not to do something like that, and assured him that he would be observing carefully for anything that might jeopardize Dale’s right to a fair trial.

TRIAL BEGINS

The next morning, we took our positions and the selected jury members entered the courtroom. Dale greeted me with a grunt and the court called the case to order. The state presented their opening statement and painted Dale as a violent man that threatened a witness to keep that witness from testifying, he did it for one reason and that was to thwart justice for his own gain. He was a bad man, a man that even his own mother wanted nothing to do with.

I had decided that we would focus not on Dale, but rather exactly what happened in the courtroom that day, and more importantly the twenty years’ worth of hatred that these two men had for each other, equally, before the incident in that courtroom. The task of laying out that story would fall to my associate, and he was going to be standing in front of a jury for the first time.

Despite his understandable nervousness he delivered the story well. He set up the relationship between Dale and the witness, Mr. Permenter. Jared concluded by acting out for the jury how Mr. Permenter was forcibly removed from the courtroom and forced through the door. He captured the juror’s attention and set the stage for our defense, a defense that did not include a demonstration of how Dale Roland would have been restricted from making the gesture, but rather that he made the gesture, but did not violate the law as he was charged.

When I decided that I was going to commit myself to Dale’s case I also had to commit to a very different defense than I had originally planned. Dale was clear that he was not wearing handcuffs on that day and could have very easily made a throat slashing gesture. The question the jury was going to have to decide was whether that gesture had placed the witness [Permenter] in fear for his life, that he had been intimidated. I would argue that he had not been intimidated and was therefore not guilty of the felony for which he was facing life in prison. The key to this defense would rely on the testimony of Mr. Permenter himself.

Dale’s brother-in-law, Michael Permenter took the stand to testify as a victim of witness intimidation for the state. During his direct examination, he explained that he had taken the stand that day to do his duty and testify against Mr. Roland. He described how as he was leaving the stand he just happened to look in Mr. Roland’s direction and saw him make a throat slashing gesture. When he saw this he exclaimed, “I don’t have to take this” and began moving in Mr. Roland’s direction before an officer stepped in his way and then he left the courtroom. He testified how he called the jail nearly every day to make sure Mr. Roland remained in jail and had not made bond. He testified that he had trouble sleeping and feared that if he were released that Dale would in fact harm him. When he was asked to explain why he would appear and testify today, he mentioned that he still felt it was his duty and that everyone was better off with Dale being locked up.

This was not the first time I had cross-examined Mr. Permenter. I knew how much he hated Dale, and that he was a prideful person. I started by acknowledging the difference in stature between the two men, Dale is much smaller. I then began to explore their relationship that had expanded over two decades. I asked about arguments that they had said. These two men had said mostly hateful things to each other ever since Mr. Permenter had married Dale’s sister. With his help, I explored one incident that included him kicking Dale out of his car and making him walk home after leaving a funeral service for Dale’s father.

I questioned Mr. Permenter about another incident in which an argument between the two turned physical. Despite all the threats and arguments between the two over the years it was the only argument that ever turned physical. With my assistance, Mr. Permenter explained to the jury how he had grabbed Dale and threw his against a wall. When I suggested that Mr. Roland could have gotten the upper hand on Mr. Permenter physically in that instance, he was quick to correct me that he in fact was the aggressor and always had the upper hand. From there I moved on to the throat slashing incident itself.

I set the scene and again with Mr. Permenter’s assistance he described how he went to attack Mr. Roland after he made that gesture. Not only was he stopped by the officer, but he was forcefully removed, and from the way he described it, to the benefit of Mr. Roland’s safety. After Mr. Permenter finished telling of his feats of machismo, I turned and explored this tremendous fear he claimed to have of Dale Roland. I finished by proposing that he was here motivated not so much by his duty to do the right thing, but rather by his hatred of his brother-in-law and his desire to see bad things, like a life term in prison, happen to him. He was adamant that was not the case, but I was confident that the jury paid as little attention to his answer as I did.

The state next called the officer that had been in the room and witnessed the gesture by Mr. Roland and the reaction of Mr. Permenter. He had been in the courtroom during Mr. Permenter’s testimony and his own account of events showed that he was paying attention. He painted a very different picture of what occurred, and explained that he did not have to remove Mr. Permenter at all. Having followed that testimony, the officer’s account almost felt self-serving to the state and was exponentially different than that of their star witness. Mr. Permenter’s account just sounded more believable, and when the officer was done the jury was left with two very different tales presented by the same side.

The final witness for the state, to my shock and amazement, was a jailer. He was the Sherriff Department’s officer on policy and compliance. He demonstrated how shackles and belly chains were applied to an inmate. He demonstrated the range of movement that an inmate would have. Up to this point it was only the witnesses for the state that had testified that Mr. Roland was wearing these chains during this incident. I did not ask this question because my client was insistent that he had not been wearing all this. It was the state that asked for and received this testimony. And it was the state that called this witness to demonstrate that someone chained in this manner could in fact bring their hands to their throat and making a slashing gesture.

On cross-examination, I honored my client’s wishes and did not explore the difficulty that being shackled would create for someone that wanted to make a gesture like this. I kept my promise. Dale had told the prosecution prior to trial that he wasn’t chained, he could have done what they said he did, but just like everyone Dale had ever encountered in his life, they didn’t listen to him. I did listen to him, and instead I took a different route.

I asked the deputy what the purpose was of these chains and shackles. He replied that it was to ensure that the inmate was rendered safe. “Safe from what?” I asked.

“Well, that everyone is safe from him,” the deputy proclaimed.

The deputy explained that an inmate could raise his arms up to a point but was unable to reach his arms out. As we continued I was able to get the deputy to describe how an inmate would be vulnerable to someone doing something to them, but they could not retaliate or defend themselves. When the deputy concluded his testimony, he had accurately described a scenario in which Mr. Permenter could have attacked Dale and Dale would not have been able to do anything about it. It was a good thing the other officer was present to protect Dale from being harmed or injured by Mr. Permenter’s fury.

CLOSING THE TRIAL

Criminal defendants are entitled to what are called lesser-included offenses at trial. When requested a jury may consider a lesser-included offense if the is a question that the defendant may not be guilty of the crime they are charged with. A lesser-included offense may be a crime that carries less punishment, but fits with the facts presented at trial. Prior to the close of the trial I had requested that the court give the instruction on the lesser-included offense of “Threatening to Preform and Act of Violence”, a misdemeanor that can only carry up to six months in jail. This was the same crime that I requested that the state allow in a deal for Dale to plead guilty.

Over the state’s objection the court granted my request. Joe Watkins argued to the jury, that Dale was the worst kind of criminal. He was someone who attacked the very structure of the justice system itself, he tried to prevent someone from testifying. He implored the jury to send a message to all those that would consider such a horrifying course of action. The jury could give this man life and they should consider doing just that. He was a career criminal, he needed to be locked up forever.

I approached the jury, and took a deep breath. I had an idea what I wanted to say, but I still had not figured out how I was going to start. So, I just started.

“I don’t like Dale Roland. That hasn’t changed. I can understand why anybody would not like Dale, that makes sense to me. You still can’t find him guilty.”

I explained to the jury that this incident wasn’t what the state wanted to believe, and it wasn’t what they wanted the jury to believe, this was two decades worth of two people hating each other. Michael Permenter wasn’t scared or intimidated by Dale Roland when he went after him, he wanted to beat him up. And if it wasn’t for the officer intervening he would have likely succeeded, the state’s last witness told us how vulnerable Dale was that day.

I empowered the jury by telling them that they got to have the final say, not the government. They got to decide how this whole thing ends, they got to set things right, and the law would allow them to do so. I pointed to the lesser-included offense and argued that Dale was entitled to be treated under the law just like anyone else. The state doesn’t just get to throw him away forever because he had a past, he has earned the right as a citizen to be judged under the facts and applicable law like anyone else, and anyone else would have never faced a charge like this under these facts.

Mr. Watkins followed me with the state’s final argument and crossed the line to the point I had to object, putting Dale down and literally calling him names. He spoke about him as if he were speaking about trash. I felt like the argument was petty and uncalled for, but I did fear that it might be effective. I had been honest with this jury, I told them my personal feelings toward my client and they were not good. I was afraid that might hurt Dale, but I felt if I had done/ anything else it would be dishonest.

It would be about twenty minutes of waiting before the jury reached its decision. Dale only grunted as the jury found him not guilty of Intimidating a Witness and guilty of the lesser-included as I had requested they do. The jury recommended the maximum sentence of six months.

CONCLUSION

Because of this trial I was able to get Dale a plea of time served on his other case involving the “medical marijuana”. I was proud of the result of this trial. It was a victory for my client in every sense of the word, but it was what Dale gave me that I’m most grateful for.

My feelings have not changed for Dale. I purposefully left out a lot of things that were said during what conversations we had both before and during the trial. I have done so for two reasons: first, because it was mostly just cursing and vitriol, and because I already told you I didn’t like him, and that’s good enough. Second, I got a glimpse of something terrible. I got to witness some of his pain, what he was willing to let me, and I will keep his confidence.

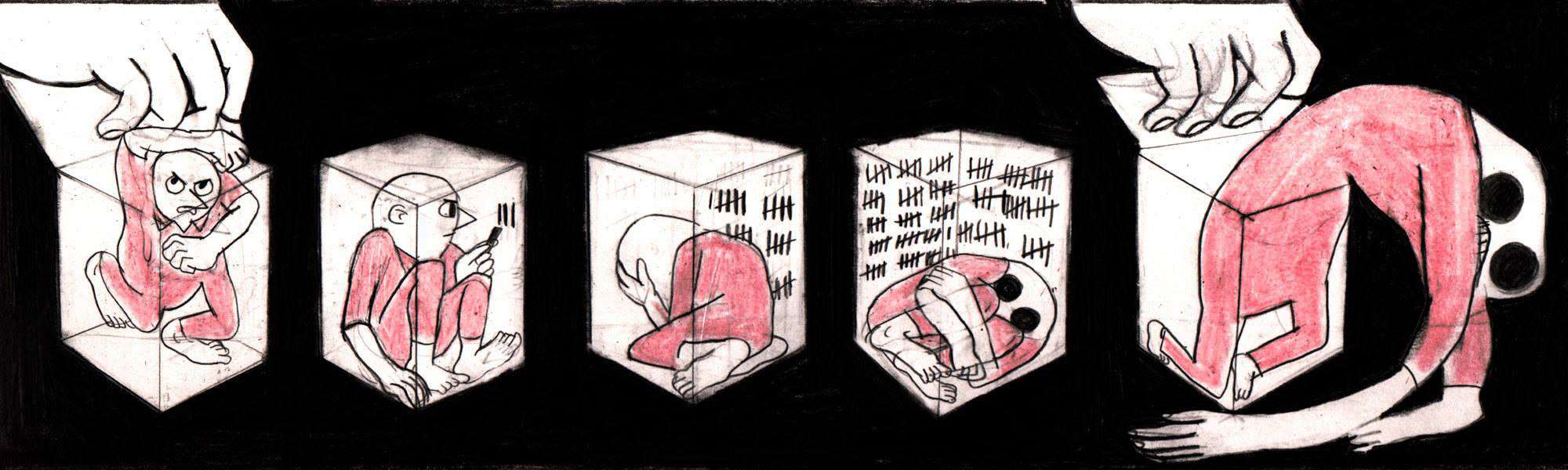

Nobody has listened to Dale his entire life, and neither did I. I discounted whatever he wanted to say to me, probably fifty years’ worth of what he wants to say to anybody who will listen to him. He has lived most of his life in confinement, and it can be assumed that he has been exposed to abuses that we could not began to imagine. Society threw him away, discounted him as garbage at a young age, and he has clawed back to gain whatever life he can ever since. He told me some things that morning before the trial began. He talked to me about his life and the people that have been a part of it, I had just a glimpse of the pain that he has endured. I waited too long, but I did eventually listen, and I know that buried under all that pain is a soul deserving of respect and even love.

I am ashamed of the way that I melted into the version of every other person that Dale had ever come across. I refused to listen. I made a mistake, and Dale Roland showed me that. Jesus and John Lennon…

No Comments